Introduction

Rudyard Kipling’s Kim brings out a wide range of reactions upon analysis. Those reactions range from outrage at the blatant racism (perceived in the text) to adoration (for Kipling’s knowledge and seeming love of India). Scholars have argued that Kipling’s seeming vast knowledge (which ordinarily would be a plus in a novel) is too overshadowed by his imperialistic attitude toward the Indians. Rudyard Kipling’s Kim paints a story of a young orphan boy of British descent who behaves and looks almost wholly Indian. Kipling’s narrative of Kim at first seems benign with regards to racism and imperi alistic attitudes but as the story progresses you can see that Kipling is sure to remind readers that this boy is white and therefore better than the Indians who have influenced and raised him. Sometimes it’s as subtle as a gesture of help that a native doesn’t need to as blatant as Christianity being represented as the only correct religion. One could argue that Kipling’s love of India does come out at times to attempt to give a more balanced view. There are episodes in the novel in which Kipling’s narrative shows a contempt for British culture by describing it as dull, lifeless, and cruel juxtaposed against the more serene and polite Indian culture. The sometimes sympathetic portrayal of the Indians has been trotted out as proof that Kipling was not an imperialistic racist. In fact, in the scenes in which Kim is with the Lama, it shows a different side, a more empathetic and spiritual side but unfortunately for Kipling, however, The Great Game plays a much bigger role. The Great Game is all about imperialism and suppressing a lesser culture so that the greater culture AKA the British, can help the natives become better, but really it’s about power and control.

alistic attitudes but as the story progresses you can see that Kipling is sure to remind readers that this boy is white and therefore better than the Indians who have influenced and raised him. Sometimes it’s as subtle as a gesture of help that a native doesn’t need to as blatant as Christianity being represented as the only correct religion. One could argue that Kipling’s love of India does come out at times to attempt to give a more balanced view. There are episodes in the novel in which Kipling’s narrative shows a contempt for British culture by describing it as dull, lifeless, and cruel juxtaposed against the more serene and polite Indian culture. The sometimes sympathetic portrayal of the Indians has been trotted out as proof that Kipling was not an imperialistic racist. In fact, in the scenes in which Kim is with the Lama, it shows a different side, a more empathetic and spiritual side but unfortunately for Kipling, however, The Great Game plays a much bigger role. The Great Game is all about imperialism and suppressing a lesser culture so that the greater culture AKA the British, can help the natives become better, but really it’s about power and control.

“Kipling’s ‘Kim’ demonstrates how he misrepresents the cultural condition of late nineteenth century India in order to maintain and exert the strength and validity of British imperialism. Kipling’s vivid descriptions of the hegemonic relationship between the natives and British settlers is important. By considering Kipling’s life and his craftsmanship as a journalist, it is evident that how he is enthusiastic about authority of colonial discourse and imperialism. Kim is a stereotypical description of the Indian people. The British imperial power demonstrates the Asiatic people as lazy, foolish, uncivilized, childlike and superstitious who need the help of Europeans” (Ghiasvand and Zarrinjooee 1688).

Kim’s role in the Great Game clearly reveals Kipling’s unquestionable devotion the rightness of the British Empire and the hegemonic systems in place that were meant to oppress and control the native Indians by placing them in a position of subordinate or Other and the British Empire as superior.

Cultural Relativism, Racism, and Otherness

As mentioned in the introduction, there have been many debates over the racist/imperialistic content in Kim. So the question that should be asked is “Was Kipling a racist and therefore making Kim a racist/imperialistic text?” or “Is is just the text just racist/imperialistic and not its author?” And why should we care? Edward Said indirectly answers this in his introduction of Kipling’s Kim.

“…whether we like the fact or not, we should regard its author as writing not just from the dominating viewpoint of a white man describing a colonial possession, but also from the perspective of a massive colonial system whose economy, functioning and history had acquired the status almost of a fact of nature…The division between white and non-white, in India and elsewhere, was absolute, and is alluded to through Kim: a sahib is a sahib, and no amount of friendship or camaraderie can change the rudiments of racial difference. Kipling could no more have questioned that difference, and the right of the white European to rule, than he would have argued with the Himalayas” (Said 10).

No matter what we feel about Kipling’s text of Kim, it is important to remember that similarly to Kinglake and his Eothen, Kipling could not have simply broken free from his cultural constructs and wrote as if his whole life never happened. He wrote from what he knew and believed. It doesn’t change the fact that this text is overtly imperialistic and the native characters are almost always depicted as inferior needing white man’s assistance. This insistence in the novel to remind the readers often of the Indian’s inferiority, is just one of the ways that native population becomes Other. So what is Otherness and how is it represented in Kim? Otherness is cultural construct created by unevenness of power. It where the hegemonic class/race/ethnic group oppresses a group from a position superiority and power. Kim, as racially white, can dress however he wants but at the end of the day he knows he is white and wields that power which he demonstrates in the first chapter. “Off! Off! Let me up!’ cried Abdullah, climbing up Zam-Zammah’s wheel.Thy father was a pastry-cook, Thy mother stole the ghi,’ sang Kim. ‘All Mussalmans fell off Zam-Zammah long ago! Let me up!’ shrilled little Chota Lal in his gilt-embroidered cap. His father was worth perhaps half a million sterling, but India is the only democratic land in the world” (Kipling 5). Right at this point Kim asserts his supremacy as a white male, yet, he before and later he will associate and behave more Indian than white when it suits him.

The question of racism and why we care can be answered by looking at this poem written by Kipling.

“WE AND THEY

All good people agree,

And all good people say,

All nice people, like Us, are We

And every one else is They:

But if you cross over the sea,

Instead of over the way,

You may end by (think of it!) looking on We

As only a sort of They!” (Kipling n.p.)

“We” signifies supremacy and “They”, as always signifies otherness. Kipling’s inability to see beyond his own cultural lens, makes this poem seem even more imperialistically racist, particularly if the reader is Asian. Perspective is everything in literature analysis and cultural relativism dictates how we see it. Kipling was no different. “We and They” could very well be perceived as racist by those in with the greatest epistemic advantage. From the perspective of standpoint theory, with regards to Kipling’s writings (particularly Kim, “We and They”, and “White Man’s Burden”), that would the natives. Their perspective and perception maintains the clearest picture of reality because they are consistently the Other. Another example from the text of Kipling’s view on Indian inferiority (read: racism), is this quote from the beginning of the novel.

“Though [Kim] was burned black as any native; though he spoke the vernacular by preference, and his mother-tongue in a clipped uncertain sing-song; though he consorted on terms of perfect equality with the small boys of the bazar; Kim was white—a poor white of the very poorest. The half-caste woman who looked after him (she smoked opium, and pretended to keep a second-hand furniture shop by the square where the cheap cabs wait) told the missionaries that she was Kim’s mother’s sister; but his mother had been nursemaid in a Colonel’s family and had married Kimball O’Hara, a young colour-sergeant of the Mavericks, an Irish regiment” (Kipling 1).

The insinuation is being ” burned black as any native” is inferior to being white, male and British, because Kipling is saying Kim can choose to behave Indian but he not Indian whereas an Indian, just is. He makes sure to assert Kim’s genealogy from the very beginning to keep a level of separateness between Kim and other natives. Why should we care if a writer is a racist or just a victim of cultural relativism? Changing how literature on others cultures is represented it. It would be the first step towards true representation and not cultural appropriation, something Kipling had Kim performing before there was a term for it. In order to succeed at the Great Game, Kim consistently appropriated the Indian culture and/or then abandoned it whenever it suited him.

Espionage in Kim

“But what he loved was the game for its own sake,”-Kim, Rudyard Kipling

Kim’s Participation in the Game

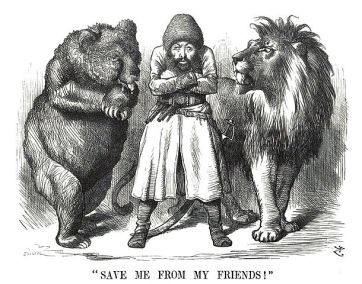

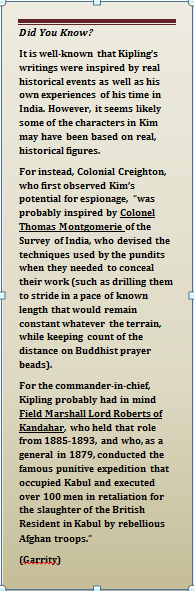

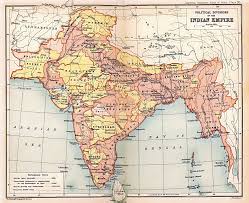

Though it was published in 1901, the action in Kim is set about ten years prior to that, during the period when The Great Game was at its peak. “The Great Game” refers to the rival attempts of the Great Britain and Russia to gain control of Asia throughout much of the 19th century. At the time, Britain already considered India to be the “jewel in its crown,” but Russia was seeking to expand its own, already considerable, empire. Acting as a “buffer zone” between these two powers were Persia, Afghanistan and Tibet (Garrity). As the below cartoon from 1878 might indicate, things were a bit uncomfortable for the Persian, Tibetan or Afghan native who was forced to exist between two, somewhat predatory “friends,” Russia (represented by the bear) and Great Britain (the lion).

The Great Game was also made up of a complicated inner web of espionage which not only enlisted British and Russian intelligence, but also numerous natives who joined in the covert battle for control. For the Brit enjoying a position of power abroad, the threat therefore came not just from Russia, but also from within: “The (British) raj followed closely rumors of Russian-paid agents who were working to undermine the loyalty of problematic Indian military units and native princes who had their own private forces. British authorities, meanwhile, sent agents to work throughout India and beyond the frontier to collect intelligence and disrupt enemy plans” (Garrity).

Kipling’s book Kim is set in the midst of this historical “Game,” with the main character finding himself quite in the middle of it all. “Kim,” (Kimball O’Hara) is an Irish orphan who has grown up as an Indian native. From the very beginning of the book, the reader learns about Kim’s curiosity, stealth and sense of adventure. Kipling writes: “But what he loved was the game for its own sake-the stealthy prowl through the dark gullies and lanes, the crawl up a waterpipe, the sights and sounds of the women’s world on the flat roofs, and the headlong flight from housetop to housetop under cover of the hot dark…The woman who looked after him insisted with tears that he should wear European clothes-trousers, a shirt and a battered hat. Kim found it easier to slip into Hindu or Mohammedan garb when engaged on certain businesses” (6). The “game” in this passage doesn’t refer to “The Great Game,” rather to the way Kim views his own, personal escapades.

Even so, this description of Kim gives the reader insight into several qualities that will make the title character adept in espionage. Not only does he enjoy the thrill of secret adventures, he is also skilled at blending in; he speaks several languages and may pass for Hindu, Mohammedan or English. Kim’s adventures begin after he decides to become a Tibetian lama’s ”chela” (disciple) and accompany the lama on his quest to find Buddha’s “River of the Arrow.” Before Kim sets off, Mahbub Ali asks him to deliver a package to a British officer while he is on his journey. This package, which Kim will deliver to Colonel Creighton, contains a message of warning from Mahbub, who is actually an undercover agent.

Kim continues on with his journey, but Colonel Creighton will later recognize his potential as a spy and help him on his training. After Kim’s heritage is discovered, he is sent to St. Xavier’s school (a much better alternative than an orphanage). While he is educated at St. Xavier’s Kim also continues to learn on his vacations as he trains in skills that will be necessary in the Great Game. When he is ready, Kim embarks on several missions to unfurl Russian attempts for control. While he is successful in his missions, they do take a toll on him.

The book ends with Kim and the lama, whom he is able to see fulfill his quest for the “River of the Arrow.”

Questions of Identity, Imperialism and Hybridity Presented by the Game

At the end of the novel, Kim may appear to have found his purpose in espionage. However, it also seems that he is still at somewhat of a crossroads regarding his own destiny. In fact, Kim’s identity, as questioned and enlightened through his role as a spy in The Great Game, is a prominent theme in the story. At the beginning of the novel, he is something of an in-between, known by others as “little friend of all the world.” By becoming an agent in The Great Game, however, he has made ties and an allegiance to the British Empire. Does this mean that he has embraced his Irish heritage and now only dons “Kim the Muslim” or “Kim the Hindu” as one would wear a mask? Or will these other identities always be a part of the real him? How has the Great Game shaped this boy into the young man he is becoming by the end of the novel?

One perspective is given in the Chapter, “Kim Could Lie Like an Oriental”- in which Danijela Petkovic writes: “the heart of the novel—the answer to the question ‘What is Kim?’ that the boy repeats time and again-is ultimately inseparable from imperialism.” Many critics, like Petkovic, believe that Kim’s choice to become a spy for the Empire, and the fact that he takes advantage of his Irish heritage in order to receive the education at St. Xavier’s to do so, indicate that “Kim’s identity is, in the end, inseparable from the British Empire and generic imperialism…he is an Irishman serving in the British Secret Service, helping it to keep India, the synonym for the British Empire, under control” (Petkovic 34). The fact that he tries on different disguises and cultures is, in this vein, considered attributable to adolescence, as all young people experiment with different identities (Petkovic 35). Another piece of evidence Petkovic utilizes to support this perspective is the opening lines of Kim:

“He sat, in defiance of municipal orders, astride the gun, Zam-Zammah on her brick platform opposite the old Ajaib-Gher—the Wonder House, as the natives call the Lahore Museum. Who hold Zam-Zammah, that ‘fire-breathing dragon,’ hold the Punjab; for the great bronze piece is always first of the conqueror’s loot. There was some justification for Kim-he had kicked Lala Dinathanah’s boy off the trunnions-since the English held the Punjab and Kim was English,” (Kipling 4).

The argument here that Petkovic makes is that the very first image given to the readers in this book is that of Kim asserting dominance over a native child, and feeling the right to do so because of his English heritage: an image which many would attribute to Kim’s, already inherent, identity as an imperialist.

Others however, might, look at these initial lines and take an alternate perspective about Kim’s concept of self. In her book, Ambreen Hai re-examines the opening of Kim in the chapter “The Doubleness of Writing (in) Kim, or, the Art of Empire.” This chapter points out that, while these lines in Kim may symbolize his identification with “the white child’s superiority,” the text also indicates that he sits, “’in defiance’ of colonial government and authority, occupying a position all his own, straddling the gun, in a position of in-betweeness” (58). In other words, though Kim may feel himself superior due to his Englishness, he is not quite English either. He defies the rules, and perhaps the reason for this is because of his own hybrid nature. In this way he is neither colonizer nor colonized, but something new and in-between.

The concept of Kim as an in-between sort of protagonist ties into the concept of hybridity, a significant post-colonial term which refers to “the intermixing of cultures that has occurred as a result of colonialism. Its full meaning in contemporary discourse is grounded in the theories of the major postcolonial theorist Homi K. Bhabha, who conceives of hybridity as a “third space” in which cultural identity is negotiated in a way that subverts the power relations beween colonizer and colonized” (The Encyclopedia of Literary and Cultural Theory).

In Hai’s reading of Kim, the theme of hybridity continues even after Kim accepts his position under the British Empire. She points to the harshness of the Game, the toll it takes upon Kim, and uses this to describe an inherent juxtaposition-or ‘doubleness’- between the title character, “Kim,” and the text itself, Kim. Her argument ultimately claims that, “whereas Kim the character ends up a secret agent in the sense that he is an agent for the empire, Kim the text suggests that it may itself be a secret agent in another sense. As it depicts the working of the imperial system, Kim also demonstrates, without being entirely subordinate to the system, the negative effects of the induction of Kim” (96). This theory would make the work itself a hybridized text which uses Kim’s quest for identity to both embrace and rebel against colonization.

It is especially interesting to consider both of these perspectives on Kim’s identity in light of Kipling’s own background. Kipling loved India and spent several years of his life there. He spoke the languages and knew the culture, and all of these things come through in his vivid descriptions of place and character. Despite this, however, Kipling was also a well-known imperialist who supported the undertakings of the British Empire and penned the infamous, “White Man’s Burden.” Furthermore, while many of his texts do contain more evident support of imperialism, the perspective in Kim is uniquely, “different in spirit…Kim (surprisingly) gives voice to tensions and ambiguities with regard to British imperialism and the Indian ‘subjects’” (Petkovic 40). Whether you find Kim to be an imperialist or a reflection of hybridization by the end of the novel, it cannot be argued that this text presents complicated ideas and questions about identity through the main character’s participation in The Great Game.

Kim’s Game

&

How to Play it

|

“ ‘But what is the game?’ ‘When thou hast counted and handled and art sure that thou canst remember them all, I cover them with this paper, and thou must tell over the tally to Lurgan Sahib. I will write mine.’” |

What is Kim’s Game?

One of the activities used in Kim’s training is now widely known, even today, as “Kim’s Game.” When it is first introduced in the book, Lurgan Sahib tests Kim against a rival child to see which can remember the details of fifteen stones on a tray after looking at them for only a short amount of time. Kim is bested by the boy, who recalls intimate details about each stone—not just their color, but their weight, also, and any flaws or differences perceived in each one. The game itself, based on the principals of detailed observation and memory, is actually quite straightforward. To get a visual on Kim’s Game, check out this clip from the film version of the book, which was made in 1950:

Clip:

As we all know from most spy films (or, from my personal favorite detector

As we all know from most spy films (or, from my personal favorite detector

Sherlock Holmes), there is almost nothing as important in espionage as keenly honed powers of observation.

In order to boost your observational skills, try your own version of Kim’s Game at home!

How to Play “Kim’s Game” Anywhere:

Really all you need is: a collection of eclectic items (just about anything will do), something to cover them up with, and partner to ask you probing questions.

You can even try it from the comfort of your computer. Take a few moments to glance at this picture. Questions will follow, but don’t skip ahead—not fair!

Here are some items that were in my kitchen. Simply take a few moments to observe what you can about the image.

Got it? Scroll down so the picture is out of view now….

Keep going……..

Okay, that should do.

Now, without cheating, see how many of these questions you can answer.

- How many objects are there altogether?

- How many shadows can you see?

- How many teabags are in the picture?

- What color/s are the teabags? How many of each color?

- How many shells are there? What kind?

- Which has a larger circumference: teapot or candle?

- Can you name three colors that are on the teapot?

Ok, now check your observations by looking at the picture again. How did you do? This particular image was fairly simple, but you may have found it more difficult to recall the details than originally anticipated. If you remembered everything, good for you! You might be missing a career as a spy….or are you?

Wait, don’t tell me…I don’t want you to have to kill me.

Spirituality & Respect

And so we wonder about spirituality in Rudyard Kipling’s ‘Kim’ and we look for hidden meanings and messages when perhaps the most obvious is simple balance.

Kim features Muslims, Buddhists and Christians, as well as three or four other religious dialects and faiths in a melting pot story that seems to hammer home the point that none is greater than the other – but that they all have merit. The very definition of spirituality – according to Google – is ‘a broad concept with room for many perspectives. In general it includes a sense of connection to something bigger than ourselves and it typically involved a search for meaning in life. As such, it is a universal human experience and something that touches us all.

In Kim – with the various faiths coming in and out of focus – the message seems to be ‘to each his own and none is greater than the other.’ Kipling seems to pay homage to religion by introducing so many faiths, but he doesn’t seem to put one above the other. Instead he seems to focus more on the ability of them all to exist on the same level as long as they are grounded in decency. There is a pervading sense of the importance of ‘doing the right thing’ – whatever that might be.

‘At the gates of learning we were taught that to abstain from action was unbefitting a Sahib.

And I am a Sahib…’ (Kipling pg. 167)

A ‘Sahib’ is a title for a man of respect of honor – hence, do the right thing.

Even those without a religious faith – or a weak one – still seek this meaning as we saw when a group of soldiers looked to a young Kim for guidance and understanding simply by his presence among them. A woman even fed him when, after looking upon him as some sort of sage, he promised that her husband would return home from the war.

We’re all looking for something…

But we also learn that a religious faith can sometimes supersede other priorities such as political footholds and war-time advantages. To counter that, we have that love of country and duty that serves as the trump card. That decency mentioned above smacks head-on against the needs of a nation looking to overpower, outwit or control another.

The key, as it always seems to be, is how to strike some type of a balance.

Alessandro Vescovi, in his text ‘Beyond East and West: The Meaning and Significance of the Great Game,’ touches on that balance as well as the unending wrestling match with it:

‘This is how, at the end of the novel, the hero comes of age, not to abandoneither spiritual or practical life, but to live through it with the detachment that comes from the knowledge that practical life is ultimately an illusion. During his formative years, Kim is indeed poised between practical and spiritual life but there is no evidence that he cannot find a balance as an adult.’ (Vescovi pg. 3)

With regards to spirituality in the Great Game – where exactly is it? Kipling introduces various religious preferences, but he keeps them at bay enough so the reader is aware of them and ultimately aware of their irrelevancy in the grand scheme of things. Any concept of a greater good – a sense of purpose beyond us – is overwhelmed by the paranoia and the struggle that takes place regarding Great Britain’s fear that Russia was making a move on Asia. What he seems to be looking for is someone with the moral fiber and strength to engage in these conversations without a nod towards such a power starved agenda.

And Kim, with so influences in his growth into a man, might be the one to do that.

‘Kim, therefore, seems to have both the intellectual and moral standing to

handle truths that are above the other people – be they practical or spiritual.’ (Vescovi Pg. 5)

In the end, though, will it ever be enough?

It’s my contention the Great Game didn’t have room for spirituality – unless it could be used as a weapon of leverage in the exhaustive battle for ‘world domination’ and political gain. Who has time or room for spirituality – for doing the right thing – when faced with taking over the world?

Other resources (to teach and learn about implications and results of imperialism)

When we talk about imperialism, racism, oppression, and the Great game, what are some of the implications? For one when you have a hegemonic system of oppression you have inequality. Second, when you have such ambitions as the British did in conquering other lands and owning them as they did with India, you have a lack of cultural understanding that in its wake leaves for more resentment and a greater wealth gap, and eventually succumbing to war. So examine to examine those issues here are questions to answer and a video to watch about what privilege does (because imperialism granted the whites privilege).

1 Based on Kipling’s descriptions and narrations in Kim, what were some of the biggest cultural misunderstandings between the two cultures that eventually led to India’s independence?

2 How does white privilege play a role in Kim?

3 Why does Kipling include religion in his novel? What is the importance?

Conclusion

In Kim, we have a story of intrigue and war between Empires, a vivid portrayal of the East as most Westerners of the time wouldn’t have known it and as no modern reader ever will. Kim paints for us a world of horse traders and holy quests and thievery on trains. Yet, while the book shows us all these things, it is really a story about a boy’s journey to manhood; “Kim” as a specific novel, produced in a specific historical, socio-political context, performs the ultimate didactic role of passing onto the young readers the dominant values of its culture. On a thematic level, this takes the form of a boy’s search for identity” (Petkovic 35).

In Kim, we have a story of intrigue and war between Empires, a vivid portrayal of the East as most Westerners of the time wouldn’t have known it and as no modern reader ever will. Kim paints for us a world of horse traders and holy quests and thievery on trains. Yet, while the book shows us all these things, it is really a story about a boy’s journey to manhood; “Kim” as a specific novel, produced in a specific historical, socio-political context, performs the ultimate didactic role of passing onto the young readers the dominant values of its culture. On a thematic level, this takes the form of a boy’s search for identity” (Petkovic 35).

Kim’s identity is tested and unveiled through his participation as a spy in The Great Game, an occupation which-paradoxically-he was always well-suited for. The questions of whether Kim is truly Imperialist in nature or whether it is trying to show readers a more complete picture of the union of East and West remains highly speculated upon, yet largely unanswered.

As readers consider this question, it is necessary to think about Rudyard Kipling’s own life and the way it may have influenced this novel-known by many as his most unique and best work. Despite any intentions Kipling may or may not have had in writing Kim, it seems likely that his own life may have been his own inspiration for the main character. As Kim grew up as an Irish boy in the streets of Lahore, so Kipling roamed the markets of Bombay, holding the hand of his ayah. Both experienced the culture as insider and outsider, to some degree. Both were witnesses to a myriad of different spiritualties. As Kim seems to concede to the Empire’s right to rule, so did Kipling.

However, despite that general allowance for British authority, both Kipling and Kim also exhibit something against-the-grain, something more complicated, in their plethora of cultural experiences and their love for India.

Even as Kim comes to a close, we as the readers find ourselves unsure of what will happen to our young protagonist. Which way will he go? Will he continue with the “The Great Game,” or along the more spiritual path of his good friend, the Tibetan lama? Will he grow up to be “Kimball O’Hara,” the Irishman, or will remain Kim, “little friend of all the world?” The answer is not known; instead we are left simply with the journey of the novel and the perspectives it has shown us. It is like a tapestry that is still being woven, and in this sense it reflects not only the multiple threads of culture in India at the time, but also the uncertainty of its future.

WORKS CITED

CETEL63. “Kim’s Game.” Online Video Clip. Youtube. Youtube. 3 June 2010. Web. 8 February 2016.

Hubel, Teresa. “In Search of the British Indian in British India: White Orphans, Kipling’s Kim, and Class in Colonial India”. Modern Asian Studies, 38.1 (2004): 227–251. Web.

Garrity, Patrick J. “Kim’s Great Game.” Claremont Institute. Claremont Institute, 22 Nov. 2013. Web. 7 Feb. 2016.

Ghiasvand, Fatemeh and Zarrinjooee, Bahman. “Hegemony of Empire over Orients: Rudyard Kipling’s Kim”. Journal of Novel Applied Sciences.Vol 3. Sum2. 2014. PDF.

Hai, Ambreen, and Inc. ebrary. Making Words Matter: The Agency of Colonial and Postcolonial Literature. Athens: Ohio University Press, 2009. Web.

“Hybridity.” The Encyclopedia of Literary and Cultural Theory. Blackwell Publishing Ltd, 2011. Web. 7 Feb. 2016.

Kipling, Rudyard. Kim. Lexington: Simon & Brown, 2011. Print.

Kipling, Rudyard. “We and They”. The Essential Rudyard Kipling. Amazon free publishing. 2014. Kindle.

Petkovic, Danijela. “’Kim Could Lie Like an Oriental’: Imperialism and Identity in Rudyard Kipling’s Kim.”

Scott, David. “Kipling, the Orient, and Orientals: “‘Orientalism’ Reoriented?”. Journal of

World History, 22.2 (2011): 299–328. Web.

Said, Edward. “Introduction”. Kim. Lexington: Simon & Brown, 2011. Print.

Said, Edward. Culture and Imperialism. New York: Vintage.1994. Web.

Szczepanski, Kallie. “What was the Great Game?” AsianHistoryAbout.com. About.com. n.d. Web. 7 Feb. 2016.

Vescovi, Alessandro. Beyond East & West: The Meaning and Significance of the Great Game.’ From Academia.edu. 2014. Web.

Section credits:

Introduction and Otherness, other resources, and website creation: Amy Stocker

Espionage in Kim and The Great Game in Kim and How to Play it and Conclusion: Kathryn Gustafson

Spirituality and Respect: Lawrence Jacobson

Tom Brown’s School Days >>Tom Sawyer>>Kim>>Superman~ the Comic! >>Hell-Boy

+ reflection on reasons humans write a “work” =benefit students more than ‘morals’

LikeLike

But it’s also important to teach the effect of colonialism and whitewashing on those affected. 😄

LikeLike